June Blog 2022

Mixed Attaining Teaching Blog – The Sequel.

Part 1 of this Mixed Attaining blog focused primarily on “The Learning Journey” – a fundamental tool in not only mapping out the intended learning outcomes for students, but what prior knowledge needs to be considered, revisited and embedded for all student groups before moving on. As teased within the first blog on this subject, there are a number of other techniques, concepts and strategies which can be implemented, and which can work hand in hand with having a solid, well-thought-out learning journey in order to promote progressive learning within the mixed attaining classroom.

So, now you’ve hopefully had chance to digest, consider and maybe even implement some of these ideas relating to the learning journey, much like a long anticipated follow up to a summer blockbuster hit, here is the Mixed Attaining Teaching Blog – The Sequel; a summary of further teaching strategies that can help elevate the learning and teaching for all pupil groups within a mixed attaining classroom.

1. Task design and differentiation

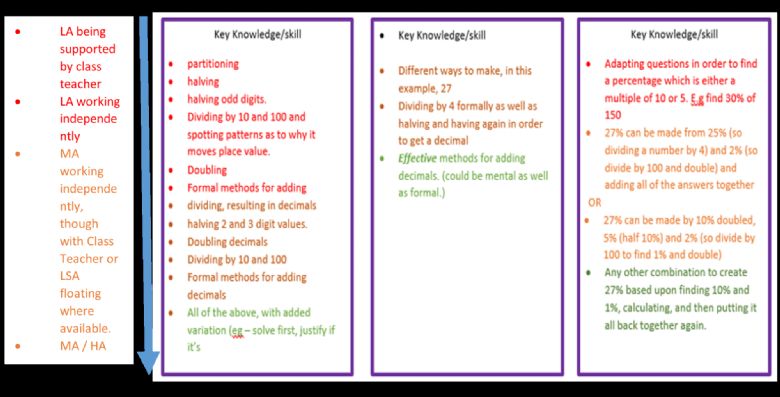

Using the same Year 7 Maths example from the previous blog, within the key skills/knowledge section (which represents the bulk of the learning journey), tasks need to be progressive; allowing students of all attainment levels to work through and embed, apply and then challenge their learning. One way of doing this could be to allow students to choose, or for you to set them off at, different starting points; middle / higher attainers could complete tasks relating to the orange or green concepts (which should be easy enough for them to complete independently, whilst still providing opportunity to stretch and challenge). The class teacher is then available to explicitly teach the LA [lower attainers]. Also, in those classes where addition adults are available, a ‘helicoptering' technique can be used just to check in specifically with any MA [middle attainers] who may need additional support as they progress through, linking to what we will later explore as flexible grouping.

Whilst differentiating tasks could appear overwhelming and contribute to a growing workload, one possible solution to this would be to make small adaptions in content. Again, using maths as an example, if all students are completing a task on finding a percentage of an amount (without a calculator), the higher attainers may do this with numbers such as 27%, which would require you to partition in a number of more complex ways, along with additional steps, whilst a child working below this level, may only need to find 20%. Here, the concepts hasn’t changed, nor has the expectation of what they are doing, but the values they may need to partition or manipulate would be more within their remit, allowing them to concentrate and develop their understanding of the concept taught, rather than the numbers or the context used. In English or curriculum subjects, this may look like removing or simplifying certain words which need to be read, so as not to change the meaning, but to reduce the level of reading skill required, should that be the student’s barrier to their learning. All adaptations and tweaks should just be enough to relieve the cognitive load, but maintain the essence of the concept being taught. Also, these adaptions, whilst widely done to remove barriers for lower attainers in the class, will actually support all students, and remove that ceiling of what teachers or other students believe either they or others can achieve; everyone is learning the same thing, though maybe just accessing it in a slightly different way. Not only does this then promote a positive mindset, through this model, all students have had the chance to progress further and deepen understanding, with HA / MA perhaps doing this more independently and with the opportunity to access deeper thinking/reasoning tasks, whilst the lower attainers are able to have explicit teaching, catching them up, ready to progress with the rest of the class. Lower attainers may not progress onto orange or green concepts within that lesson, but they are now included in the same learning journey, and able to apply this knowledge as the learning journey continues.

2. Flexible grouping, Live marking and levels of scaffold.

Differentiation and different starting points is one thing, but to really elevate their effectiveness, it is evident that the role of the teacher is crucial. As teachers, we are the most valuable resource in the classroom, so plan yourself into your lessons!

Live marking (whilst also reducing the work load of marking after a lesson) allows for immediate feedback and misconception addressing within the lesson. ‘Checking for understanding’ (CFU) tasks within lessons can greatly contribute to recognising those children who are struggling, along with those children who could be stretched further. Questioning, along with when questions are asked, should be considered early in the planning stage of a learning journey and used to stretch and challenge, assess understanding, but also pre-empt misconceptions. If you are able to recognise, but also plan for these misconceptions, teaching is more targeted and effective. Consider when you will work with certain students or small groups of students. That is not to say that you only work with certain children for the duration of a lesson, but to split your lessons up and recognise when and where your support would be most helpful. For example, you may need to spend 10 minutes supporting a LA group during a ‘Do Now’, warm up, or even ‘responding to marking’ tasks, allowing them to ‘peel away’ and work more independently as they gain confidence and understanding whilst embedding and securing knowledge the rest of the class already demonstrate. Once working independently, this could then provide an opportunity for the teacher to move to live marking work completed by MA/HA to see how they could be extended. As learning moves into the main bulk of the lesson, teachers would move on to delivering to the whole class, using questioning to decipher who may need support, and as students are set off to complete more independent work/practice (which could be differentiated in the ways already explored), the teacher would prioritise working with those students identified. A further positive to the teacher frequently working with different groups of children based upon immediate recognition of need is that it creates a culture of ‘any and all students can and will be worked with throughout a lesson’, thus creating an inclusive working environment. It again eliminates the ceiling of what each child believes they can do; working with an adult is no longer considered something only someone/the group who is struggling does.

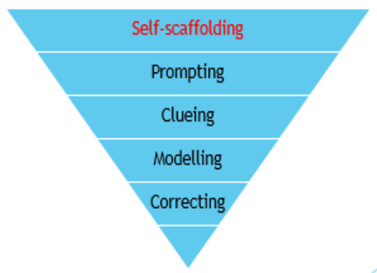

The level of support each student my need will also differ. Even though we may identify students as either lower attaining, middle attaining or higher attaining, we know that this could be for a variety of different reasons and that no two students are alike. The level of scaffold (Rosenshine) therefore also plays a key factor, not only in teaching and clarifying concepts, but allowing children to learn from teacher feedback and progress; teachers or the supporting adult is not just repeating the same models, but encouraging the child to develop and build up understanding from these models.

Self scaffolding is more suited to those HA’s or those confident in topic who are encouraged to check their own work and recognise mistakes. Adult may just direct to ‘check this’.

Prompting relies on the supporting adult drawing attention to a misconception, but limits the scaffolding. Phrases such as ‘Can you explain your thinking here?’ allows a student to develop their reasoning more and encourage self-correcting before the self scaffolding stage.

Clueing allows the supporting adult to be more direct in pointing out a misconception, but again, limits the information given to fix it. Phrases and examples such as “this part here doesn’t look right – what do you know already?” or for example, providing alternative homophones when a spelling is incorrect for a student to decide which one to use.

Modelling allows the supporting adult to model a method within a similar task for the student to learn from and apply to their own work / misconception.

Correcting occurs when the student repeatedly makes the same mistake and needs work corrected and explained the misconception in more detail. Once corrected, the supporting adult should provide one or two further, similar questions to check understanding / misconception has been addressed.

3. Resources to reduce the cognitive load.

Willingham discusses ‘cognitive load’. If information is in our long term memory (e.g. multiplication facts, spellings/spelling sounds, continents/countries, dates etc), then problem-solving using these facts will require less of a ‘cognitive load’ (essentially less brain power) than if these facts are only in our short term memory. Warm up sessions and ‘do now’ tasks can not only provide opportunity for children to either deepen knowledge or develop it, but as an opportunity to commit these concepts to our long term memory. Stanislas Dehaene’s research goes on to support the use of spoken language and verbal tasks in helping facts being stored in our verbal memory, which can be beneficial to all students, but particularly for SEND or those with reading/writing barriers to learning. Tasks where saying (and hearing) the sound pattern of the phrase, and stem sentences are important, and so should also be considered in the tasks teachers are asking students to complete, and could again be something teachers think about when trying to differentiate or create progressive tasks for students.

For some SEND, trying to commit something to memory can present its own problems. Therefore, recognising what the key element of learning is, and how you could lighten the cognitive load in achieving that can really make an impact. Having word banks, significant words or equations, diagrams etc available to students, so long as this wasn’t the key element of learning you wanted to teach / test, would help free up the cognition of students (and then could later become fluency or do now tasks in later lessons to help embed.)

Further, examples:

- An English lesson focussing on text analysis – How does the author create a sense of danger… - could be supported by word bank of synonyms. For those HA students who perhaps wouldn’t need a work bank, they could still be given one, with some red herrings thrown in, allowing for a reasoning and deeper thinking opportunity where they would need to explain why some words would be more appropriate and effective than others. Additionally, for MA, this would provide an CFU opportunity; checking that they understand the meaning of specific words, as well as potentially broadening vocabulary.

- A maths lessons on Pythagoras could be supported by word mat of squared numbers / square roots.

- A science lesson which requires table / graph plotting could be supported by table / axis already drawn. This could be further differentiated by having more or fewer things, such as titles and/or scales, already populated.

Other possible resources; word mats, word banks, pre-drawn tables, times tables grids/facts, number lines, working walls with relevant information, or which has been put up as a result of class discussion etc.

I recognise that there is an awful lot of ideas, theories and information to digest here, but I can’t stress enough that it only takes the smallest adaptation in your classrooms for all of these things to have a chain reaction; what looks like a mountain of work, only needs to start from one, well-thought-out idea or adaptation, and the rest naturally develops over time, so long as you recognise what you want to achieve next. If there is anything you would like to discuss further, whether its help designing or adapting tasks, clarifying a concept, or just to get more information, please do not hesitate to ask!