September 2019 Blog

The Writing Revolution

‘Research – particularly that of psychologist Anders Ericsson – tells us that for practice to improve skills, it has to have a specific and focused goal and must gradually link together a series of smaller goals to created linked skills.’ - TWR

A fundamental part of teaching is the innate desire to impart knowledge and experience to others. We have the great privilege of being a shaping force in a student’s life and all want to guide them towards success. The Writing Revolution (TWR) is full of methods to help synthesise the teaching of skills in small and manageable steps linking towards the greater goal of exam literacy. However, it is not just for literacy-based subjects, it can be used to help students gain order and discipline in their thought processes.

The planning and refinement of ideas is a key skill the students need in order to secure a standard pass. As soon as a sentence appears on your laptop screen you are planning its revision and refinement. Yet, this hidden phase of sentence creation comes intrinsically from many years of experience and practice, which is something our students do not have. Hochman and Wexler focus on regular repeated exercises to gradually develop the key skills needed to write fluently. Editing and adapting the construction of sentences are key to building fluent readers, writers and speakers.

The TWR’s six writing principles

- Students need explicit instruction in writing.

- Sentences are the building blocks of all writing.

- When embedded in the content of the curriculum, writing instruction is a powerful teaching tool.

- The content of the curriculum drives the rigour of the writing activities.

- Grammar is best taught in the context of student writing.

- The two most important phases of the writing process are planning and revising.

Through the writing principles, we are encouraged to plan into our MTPs the explicit instruction of sentence creation as part of the wider learning topic. By creating an expectation of writing about the topic currently studied, the students learn the grammatical skills whilst developing opinions and knowledge for their upcoming test. It is encouraged that upon introducing a new writing activity, begin by modelling and have the students practise orally so that they can first formulate the idea out loud before they need to write it down. This will encourage them to practise self-editing without the stress of written ‘failure’.

A key skill our students struggle with is understanding the difference between a sentence and a fragment. The inability to express a complete thought often derails the results of our ‘forgotten third’ as they struggle to put their knowledge into complete sentences. TWR has many techniques to help these learners and one I have found success with is providing sentence fragments from the previous lesson as DO NOWs.

Example: You may give them ‘settled near rivers’ as a key bit of information they need to remember. The students then need to draw on the content they’ve learned to provide the subject of the sentence: ‘early Americans settled near rivers’. You could further develop this with the extension of the ‘because, but, so’ exercise or alternatively include the use of subordinating conjunctions (although, unless etc.) to change the meaning of the sentence. If struggling, the students can first practice the task aloud to a partner as comprehension is often easier to develop when heard.

An offshoot of this is the difficulty of developing the detail of sentences. I am constantly writing probing questions on their work in order to get them to develop their opinions. Rather than simply providing sentence starters you can practice the ‘because, but, so’ exercise to ensure they extend their sentences.

Example: You begin with a sentence stem that is directly about your topic (Scrooge is a representation of the entitled upper classes). The students then have to expand using the conjunctions because, but and so. This not only teaches them to add extra detail to their work but also encourages them to formulate their opinions/accumulate their knowledge on the subject. If done regularly, they develop the habit of extending their sentences with specific points about the subject, leading to greater retention in understanding.

Another valuable exercise is the commonly used sentence jumble. Rather than spend your life cutting out pieces of paper simply reorder sentences that contain key information for the lesson.

Example: The students first task is to unscramble the sentences correctly before working out what the new information means. You can do this on mini-whiteboards to assist with the visual delay from working off of a central PowerPoint and the ability to erase mistakes builds confidence. They are practising the creation of sentence construction and the intrinsic skills of editing and re-drafting.

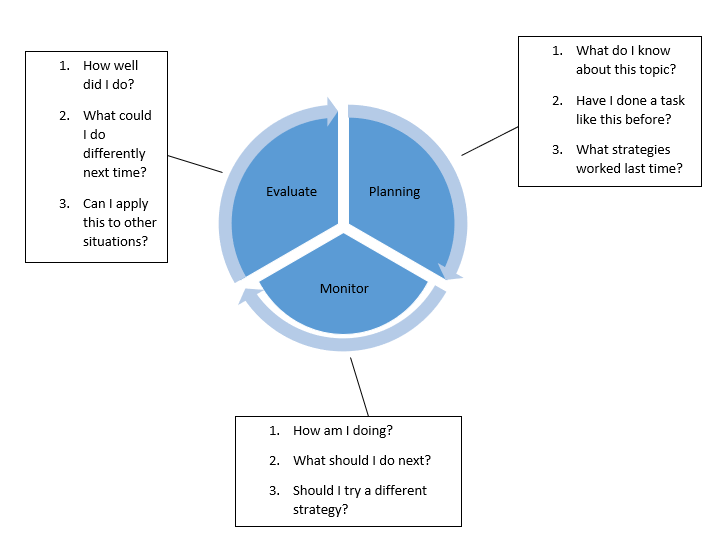

Whilst this information doesn’t stem from a new fountain of knowledge, it will help to ensure consistency throughout subjects to aid students development. Building confidence in the creation and expansion of sentences encourages the students to not only develop their writing but also their reading, listening, speaking and questioning. All key skills are tied into meta-cognition, so the more we can encourage them to actively think about their learning the more they will learn.