October Blog 2022

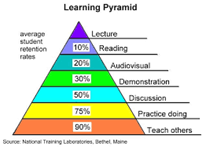

I wanted to start this blog by thanking all teachers that Tor Flynn and I visited on the Friday before half term for our learning walk. We saw some excellent practice and I was delighted that we witnessed far more student discussion and engagement with student learning through talk than we had seen previously. From all the detailed and valuable research that has been carried out on the value of oracy recently, I keep coming back to the simple, yet quite old (I remember reading about this at university so it must be old!) learning pyramid about how best we all learn.

It demonstrates that discussion, practising doing, and teaching others is by far the best way to learn something, and this is what we are seeing more in the classrooms.

I wanted to share with you all some general feedback that Tor and I discussed, and what she has seen commonly across the county on all her learning walks. I also want to share with you what a student panel thought as well.

- With ‘Think, Pair, Share’ (TPS), we often rush the process. We need to slow down and let the students think. As practitioners, we don’t think the pace is quick enough if we just stop and let them think, so often speed it up and talk over the students whilst they are thinking.

- When it comes to the thinking stage, let them jot down their thoughts on whiteboards or in their books. You will be able to tell when the right time is to move on by just watching them. Have the mini whiteboards on the desk so they are easy to grab for the students. Tim has offered to send out a video of him leading a ‘TPS’ session this half term which I think will really help us.

- When using the whiteboards for a CFU, ask them to show the boards at the same time. If they are holding up their boards at different times, it can often be the case that students check what others have put up and then quickly copy them. It is also much easier to check that everyone has put up their boards and answer when they all raise their boards at the same time.

- What happens after your CFU? There are some times when we see some excellent ways teachers check for understanding but then nothing really happens due to it. The teacher ‘ploughs on’ with their plan. I have spoken before about the values of flexible teaching, or adaptive teaching, which I believe is even easier with our new classroom layouts. An example of flexible teaching could be the following.

Teacher CFU on mini whiteboards and sees some students have not quite got the concept. Teacher sets up next part of the lesson, which is extending the thinking of the students who do understand. The teacher brings the students who do not understand the first concept to a table and moves the students who do get it to the now free seats. The teacher works with these students, and if there is a TA they can work with the students who are working on the extension task.

Tor Flynn did a really interesting student panel with a selection of our KS3 students. Much of what they said backs up our own thoughts and observations of our oracy strategies. Their key points are as follows:

- Give us time to think! We often only have 10-20 secs which is nothing. Check both partners are contributing when walking around.

- Give us some examples of sentence starters to help us start off as this helps some of us.

- Teachers check our answers, but don’t do anything with this apart from ‘well done ‘or ‘that’s not right, think again’.

- ‘They need to know what we don’t know.’ Quote from Y8!

- Live marking really helps us.

- The key words help, but sometimes the definitions used by teachers are too fancy, using words we don’t know! It’s better when they put it in a context that we will understand.

- Lots of talking over us when we are working which stops us thinking!

- We recognise we are not confident in speaking in front of the class, and need help getting better at this.

- Each teacher or subject should actually ask us what helps us, through student voice.

- Teachers are using cold calling less, and more TPS but cold calling is still good if done well. Sometimes it is just used to check the ‘naughty kids’

I think there is a lot for us to consider, but we are on the right path, and we all need to get into the right habits of doing this more in the classroom. Following on from the last point the students made, Doug Lemov (Teach Like a Champion) has written a blog about how to develop our questioning, and then getting students to think and respond to it through cold calling. This ties in directly to the points made above.

GETTING ALL STUDENTS TO THINK HARDER WITH GOOD QUESTION DESIGN

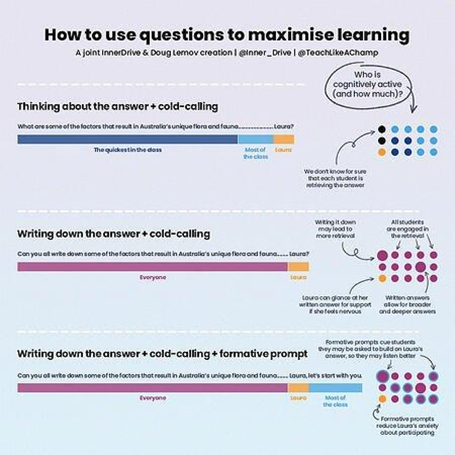

What makes a really good question? How do we ensure that we get as many students cognitively engaged as possible? And can subtle tweaks in the way you ask questions help your students feel more confident when they answer? Given that asking questions is the primary vehicle for Retrieval Practice, which continues to be one of the best bets for students learning, it is essential that we consider how to do it best. Lately, there has been a renewed interest amongst teachers for using a questioning method known as cold-calling, which is when a teacher solicits an answer from a student who hadn’t raised their hand to answer the question.

This blog (and the downloadable graphic below) looks at three different approaches to using cold-calling, with each one tweaking the structure of your question and building on the last…

THINKING ABOUT AN ANSWER + WAIT TIME + COLD-CALLING

There are certain situations where it would be beneficial to have students think of an answer to a question (instead of writing it down). These may include for younger students who haven’t developed their writing skills, for example. This type of questioning is known in the research as “covert Retrieval Practice”.

However, it is worth noting that when we ask students to think of an answer, if we tell them at the start of the question who we want an answer from, we subconsciously give the rest of class permission to switch off, as they know they are not going to be asked for an answer. As a result, they don’t have to recall the information and so miss out of the benefit of Retrieval Practice. In fact, it is likely that only the student you ask gains anything from it.

By contrast, if we use the student’s name at the end of the question, we increase the amount of time the rest of the class are being asked to recall the answer. Despite the fact that they are subsequently not chosen, more of them have still engaged in this Retrieval Practice. This means both the students you ask the question to and the majority of the class are reflecting on the task for longer.

Some worry that cold-calling can increase students’ stress levels, as the thought of being put on the spot can make them feel uncomfortable. This may well be the case if

· it is not done in a supportive and inclusive environment

· it was a one-off event

However, evidence does suggest that being part of a classroom that repeatedly uses cold-calling can actually help students feel more comfortable in participating. So, make sure to use cold-calling often to make it a norm in your classroom.

WRITING THE ANSWER DOWN + LONG WAIT TIME + COLD-CALLING

Overt Retrieval Practice is where students write down their answer to a question. So, under the right specific conditions, why might having students write down their answer be a useful strategy? There are four different, but probably related answers...

1. It helps ensure that all students are retrieving information – When students are asked to retrieve covertly (i.e., thinking of an answer), we cannot be 100% sure that they are in fact retrieving. For all we know, at any given time, students may be thinking about something else. 2. It helps the teacher asking the question to slow down and not rush their wait time – Given that there is some evidence that some wait-times are akin to the speed of an F1 pitstop, this could provide a very valuable strategy. Teacher self-discipline is a big factor in effective wait times, as it can be difficult not to jump in and solicit an answer too quickly. As it takes longer to write an answer than to say one, this helps slow down the whole process.

3. Students can cover a broader range and larger depth of information – Due to the constraints of working memory, holding an answer in your head is always destined to be somewhat limited. Writing down their answer can help students mitigate this effect.

4. Overt retrieval may potentially lead to a memory boost – If this was to be the case, it would be because of an increase in desirable difficulty, as well as utilisation of the Production Effect (which states that by producing something new with the information, students are more likely to remember it). However, it should be noted that the potential memory benefit to overt retrieval over covert retrieval is still relatively thin, with a clear consensus yet to be achieved. So, more studies are definitely needed (if you want to read some of the studies on this, you can do so here, and here).

WRITING THE ANSWER DOWN + LONG WAIT TIME + COLD-CALLING WITH A FORMATIVE PROMPT

A formative prompt is a sentence that encourages students to start the conversation. It gets the ball rolling and inspires students to share their thoughts. It can help reduce the fear of failure as perfection is neither required nor expected. It essentially lowers the stakes for the student being asked, and as such can reduce their anxiety of having been cold-called.

Formative prompts also have a secondary purpose. By phrasing the sentence as “Laura, let’s start with you” it also signals to the other students that they have to pay attention to Laura’s answer: this is just the start of the conversation, and they may be called upon to build on Laura’s answer. This ensures higher levels of concentration.

Formative prompts work best for open-ended questions. This is because formative prompts rely on students to build on each other’s answer. This would be difficult to do for factual closed questions. Therefore, you need to carefully consider the nature and format of the question you’re asking.

FINAL THOUGHTS

When asking questions in the classroom, getting your students to write down their answer, increasing wait times and using formative prompts are all strategies that, if done well, can increase student concentration, reach a sweet spot of desirable difficulty and facilitate richer classroom discussions. It definitely takes a bit longer to implement, but the learning rewards it offers make it a strategy all teachers would do well to have in their locker. This blog was co-written by Bradley Busch (InnerDrive) and Doug Lemov (Teach Like a Champion).