January Blog 2023

What is the Big Question?

The ‘Big Question’ is an innovative pedagogical tool, where instead of implementing a learning objective, a question is posed at the start of each component of learning. It is important that we share this question with the students, through our itslearning plans, so our students can get a full understanding of what they need to be able to answer by the end of this particular learning journey. There are many different research references to support this thinking which I have highlighted at the end.

Good practice indicates that we should get the students to read and consider all key words within the question. After allowing time to think, students have the opportunity to discuss their initial thoughts with their peers. Once they have consolidated their ideas, they are asked to share what they think are the important words and what these mean to them. This can act as a quick and easy form of ‘Check for understanding’ (Assessment Reform Group, 2002), where the teacher can make initial amendments to the component of learning to address any misconceptions that had not been predicted.

This dissection and analysis of the ‘Big Question’ helps to place responsibility on the students, allowing them to take ownership of this learning journey (Holligan, 2013).

How is a big question different from an objective?

The ‘Big Question’ allows the children to understand the success criteria. If they can answer the question at the end of the learning journey, they have been successful. The children have the ability to take ownership of their learning journey as they work through the components as they build up to the fuller understanding of the ‘Big Question’.

Let’s think back to our worked example in History- ‘Why did William win the battle of Hastings’. If we shared that question with the students at the start, and they discussed possible explanations, this should gain their interest and then start breaking down what they will be learning over the coming weeks. We then can then break this down into smaller components of learning based on what we need them to understand to get that fuller picture. The assessment at the end is based on the initial ‘Big Question’, so we can check learning at the end of the journey. Below is the link to the thinking template History used.

https://crookhorncollege.itslearning.com/ContentArea/ContentArea.aspx?LocationType=1&LocationID=65

When using a learning objective, teachers must generate their own questions within the lesson to support higher-order thinking. Research suggests that open-ended questions support higher-order thinking skills, but teachers tend to ask closed questions. Teachers can plan ahead using the ‘Big Question’, considering what further questions might arise as a result. Use of the ‘Big Question’ can facilitate teachers’ questioning skills, where an open-ended question can be used at the beginning of a component to initiate deeper understanding. We have encouraged this use of ‘hinge-questions’ to support our CFU points throughout a learning journey.

How is the Big Question formed, and how does this lead to components of learning?

There are several steps to planning the ‘Big Question’:

Step 1: Consider the initial learning objective. What should be learned, and what is needed for this to happen successfully?

Step 2: Identify knowledge children already hold which will allow them to be successful with this new component. An effective ‘Big Question’ will enable the teacher to make it clear to the children what prior knowledge they need to draw upon.

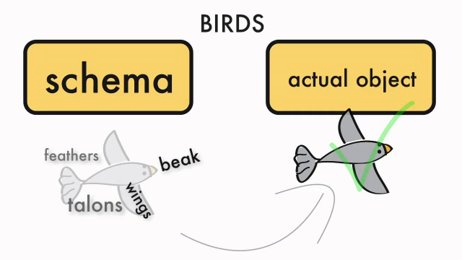

Step 3: Establish the components children will learn and understand, building on the prior knowledge to introduce new concepts or content. For those of you who were here in March 2020, we talked about the idea of schema, and how to break up learning into components. The example below comes from a ‘Big Question’ – what is a bird? We would need to break this down into the components of a bird and how all these parts make up a bird. We can use this concept with any big question we are teaching.

Once all these things are considered, a list of keywords (Tier 2 and 3) can be made and these form the structure of your ‘Big Question’ for that specific session.

An effective ‘Big Question’ will allow the students to interpret what they will be doing within that session and how they can show progression from one session to another. Therefore, it is essential that the ‘Big Question’ incorporates all the key concepts and vocabulary that will be used throughout the component.

The benefits of using the Big Question

This use of the ‘Big Question’ will improve the use of dialogic within the classroom (Alexander, 2008). This produces a positive impact across the entire curriculum where talk is an essential tool for developing and articulating understanding across a range of attainment levels.

Implications for future practice

The ‘Big Question’ promotes ‘outstanding’ teaching and learning in accordance with Ofsted (2015). To name a few criteria suggested by Ofsted, outstanding teachers should use questioning highly effectively, identify common misconceptions, check pupils’ understanding and plan lessons very effectively. The ‘Big Question’ promotes and endorses all of these criteria, allowing for constant questioning that checks for understanding and misconceptions. This innovative pedagogical choice provides us with confidence that we are giving the students the best learning experience possible and that we are supporting them in developing key skills that they will need throughout the whole curriculum and later on in life. Having seen it in practice and having witnessed its impact on both the students and the teachers within College, we believe using the big question as the basis of planning is in the best interests of the students.

References

Alexandra R (2008) Towards dialogic teaching: rethinking classroom talk. 4th edn. York: Dialogos.

Assessment Reform Group (2002) Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles [online]. London: Nuffield Foundation. Available at: www. aaia.org.uk/content/uploads/2010/06/ Assessment-for-Learning-10-principles.pdf

Crossland, J. (2015) Thinking about metacognition. Primary Science, 138, 14–16.

Dawes, L., Mercer, N. and Wegerif, R. (2004) Thinking together. 2nd edn. Birmingham: Imaginative Minds.

Holligan, B. (2013) Giving children ownership of their science investigations is easier than you might think. Primary Science, 128, 5–8.

Office for Standards in Education (2015) School inspection handbook [online]. Manchester: Ofsted. Available at: www. gov.uk/government/publications/schoolinspection-handbook-from-september-2015