Teaching and Learning Blog

By James Collins, Deputy Headteacher

- Read MorePublished 22/01/25, by Dan ParkinsonSEN focus Pam Jones has recently been asked to write an article for the HIAS team in RS where she discusses the work she has been doing to develop SEND provision in RS. She reflects on the project to explore what high-quality SEND provision involv

- Read More

November blog 2024

Published 13/11/24, by Dan ParkinsonThe value of homework As part of the College performance plans over the last three years we have been developing the idea of week-by-week homework for Year 11’s and 10EE. We feel this has been a success, especially with our improving results - Read More

October Blog 2024

Published 18/10/24, by AdminAs we approach half-term, I thought it would be good to reflect on what we have achieved as a teaching team over the last couple of years. It is important to celebrate the steps forward we have taken and how these have had a positive impact on the students we teach. You will have seen the GCSE results this summer, which are a testament to the improvements we make every day in the planning of our lessons, the feedback we give, and the quality of teaching we provide in the classroom. The feedback from prospective parents was overwhelmingly positive this term, with many parents eager to secure their child a place at our College due to our growing reputation in the community.

You will have also seen the Hampshire external reports highlighting the positive aspects of our teaching and learning ethos. All our recent staff, student, and parent feedback has been positive, which reflects the views of all major stakeholders. These are all examples of why this is a great College to work in. Thank you, and I know this is recognised by SLT, parents, governors, and any visitors we have at the College.

So, for this blog, I just want to recap on all the emails, blogs, and training we have delivered over the last few years and condense them for us all. This is nothing new, just a handy tool to help answer that internal question we all have at times: “Am I doing the right thing?”

Planning

-

Medium Term Plans are on itslearning and live for students, with resources made available for them to use. Show the students.

-

All components should be based around a ‘Big Question,’ which students should be checked on at the end. These should be matched to the curriculum map.

-

Activities should be planned to support all learners, with consideration on how to extend and support where needed. Fill out the challenge box to remind you to challenge HA students at points in those components of learning.

-

Homework should be planned, differentiated where needed. All homework must be set through itslearning, even if set through another platform.

-

Plan regular assessments to check on learning, and then consider how our MTP’s should reflect this moving forward.

-

Week-by-weeks must be planned as per the ARR calendar. We want students to know assessments are coming up and how to prepare for them.

-

We expect at least one homework and one assessment per half-term to be reflected in the assessment record on itslearning.

-

Adapt MTP’s for your class and consider how to differentiate for outliers.

Feedback and Marking

-

Feedback every two weeks in core lessons and every three weeks in foundation lessons.

-

This should include at least one piece of student work marked, with formative feedback to help the student improve that piece of work. Question-based feedback is recommended.

-

Students should respond, and the teacher should check this.

-

Mark for literacy when you do this.

-

Use live marking where possible.

Teaching

-

Welcome at the door: Check uniform and ensure the start of the lesson is orderly.

-

Have a ‘Do Now’ task ready while you take the register.

-

Go through the Big Question for this component of learning.

-

Use CFU at key points in the lesson, such as mini whiteboards, think-pair-share, or cold calling.

-

Model work through the ‘I do, we do, you do’ structure.

-

Encourage discussion where possible, following the Crookhorn rules for discussion.

-

Move around the room as much as possible. Position yourself where needed and be full of positive praise for students when you can.

-

Have your green pen in hand when moving and get into the habit of giving live feedback in the moment.

-

Differentiate in real time and adapt the lesson as it progresses, based on what you learn from CFU.

These are the Crookhorn standards, and if we all follow them consistently, we know it will benefit everyone. We are an excellent group of staff who work extremely hard to ensure we give our students the best possible outcomes. Thank you for all the hard work you put in every day to make this College the great place it is to work. Any comments or questions are gratefully received.

-

- Read More

August Blog 2024

Published 30/08/24, by James CollinsI thought it might be quite nice to write a teaching and learning blog in August when we all have a few extra moments of peace and quiet to actually sit and read rather than being in the hustle and bustle of everyday teaching life. When I sit and reflect on our pedagogy at Crookhorn, we are in a far better place than we have ever been before where classrooms are well structured, where learning is focussed, and environments are calm and well managed and where our students thrive.

The key thing for us moving into 24-25 is that we are not introducing anything new in terms of our pedagogy. Now is the time to consolidate on the structure and techniques we have been working on over the last few years and making them consistent across all our classrooms. As teachers we don’t want too many initiatives and compliance tasks that we must follow. At Crookhorn, we don’t believe in making you all do the same thing as many academy chains do, as we don’t believe this is conductive to getting the best out of you as individuals. However, there are some good evidence-based strategies that we would like to embed into your teaching that we believe help the students with their learning. I am going to highlight two of these below that we want you to consider when planning your upcoming components of learning which you have been trained on before but worth reminding you on.

DO NOW (Retrieval)

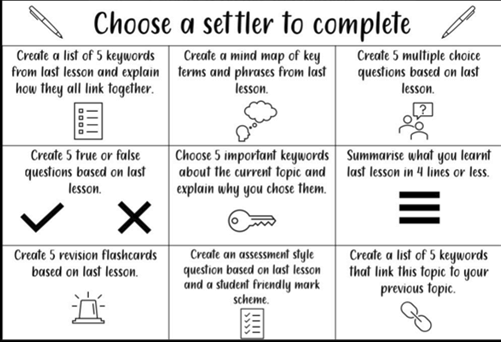

Do Now, an absolute ‘Teach like a Champion’ favourite, mixed with the idea of retrieval, which we all know is a must when it comes to moving knowledge from the short-term to the long-term memory. Below is something I stole of Twitter (I will never call it X!) which is a simple starter that we could all use to help us settle a class and build the retention of knowledge at the same time.

Hopefully you will remember the blog we did highlighting the fantastic work in science, with their ‘Blast from the past’ which asks students to remember something from last lesson, last week, last month. You could look to do something where you mix these two templates, as I do like the idea of these tasks above but not just from the last lesson. This also fits in nicely with our DBLP activities, such as flash cards and mindmaps.

Think Pair Share

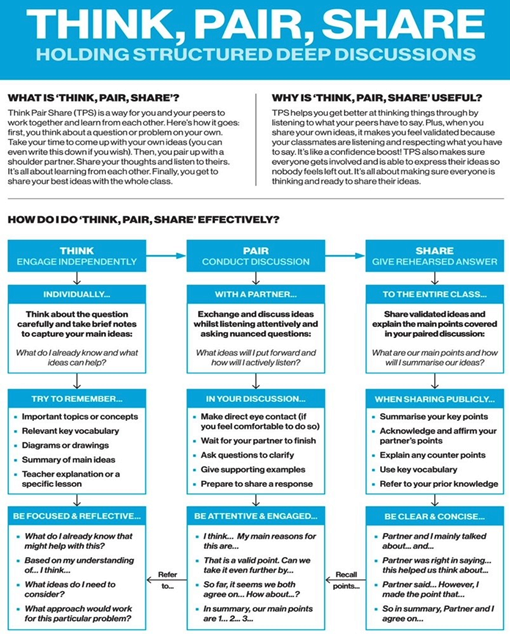

As you all know by now, I am not a big fan of the ‘hands up’ policy of questioning. The days of the teacher standing at the front lecturing the students and then checking they have understood by asking them to raise their hands to answer a question, picking on 1 or 2 and then moving on are well and truly dead. It thankfully is very rare we see that in classrooms now with far more teachers using mini whiteboards and techniques such as T/P/S to check for understanding from the whole class, rather than a few. I like this diagram above as it makes it really clear on the steps we should take when we do ask a hinge question that is vital in us understanding where the class are up to and where I am going to take the learning next. It might be worth getting this printed off, laminated and put on desks for students to use if you feel this is appropriate. The key part for me that is often neglected is the very first bit, which is the thinking part. Giving them time and somewhere to jot down their thoughts is absolutely crucial, and the mini whiteboard comes in handy here as you can walk round and look at individual thoughts, so you know who knows what!

Two keys techniques for our classrooms that we all are familiar with. Nothing new, but something we want to get right across our College. If you have any questions please do ask me or speak to your coach/mentor in your next session.

Enjoy the rest of your break and looking forward to seeing you all in September.

- Read More

April Blog 2024

Published 30/04/24, by James CollinsWhen I delivered training on adaptive teaching back in October, we used research from the EEF on what it could look like for teachers in the classroom. At the time though, it was felt that adaptive teaching was just a new term to replace differentiation. However, having persisted and done further research and also having attended a very good seminar at the ASCL conference in March this year, I can now see how adaptation and differentiation are actually quite different, and I just want to explore this a bit with you in this teaching and learning blog.

If you look at Appendix 1 attached to this blog- you will see the document, we issued on the October training day as a clear guide to what adaptive teaching looks like. The points on this document absolutely stand true as an excellent guide with one tiny alteration to the third bullet point right at the top of the document, where previously it had said ‘targeted support for students who are struggling’, it now says ‘to ensure the active engagement of all learners in the classroom’.

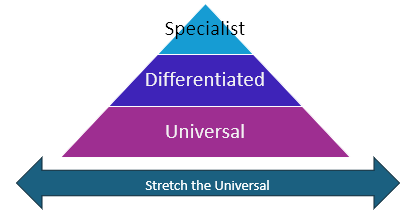

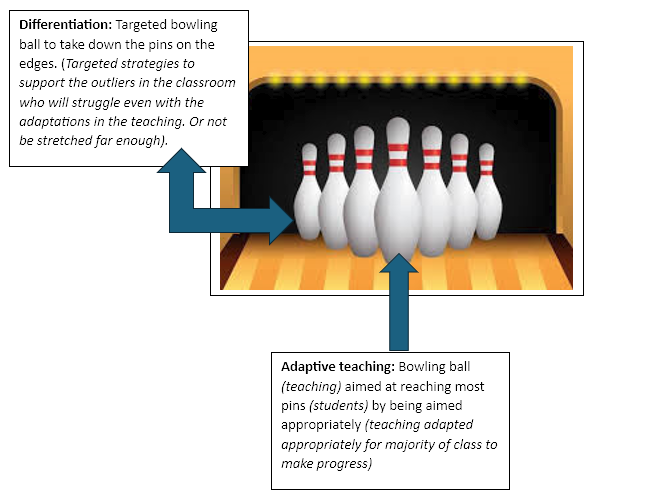

The reason for this slight tweak is for the following reason. If you look below, you will see that I have created a graphic to try and explain visibly the difference between adaptation and differentiation. Adaptation is where you adapt the learning for all the learners in your class. Differentiation is where you have to have specific strategies in place to support those who might be progress outliers in your class, either because of cognitive barriers or because of attendance or behavioural issues. The bowling alley analogy, sums this up very well.

Difference between Differentiation and Adaptive teaching

Adaptive= is adapting the curriculum or the lesson resources for the whole class (can be where you adjust a teaching resource to fit with how your class learns best, can be revisiting certain areas of information to allow for strong recall, can be dropping some tasks out or adding some tasks in.)

Differentiation= targeted support in the classroom (can be the order in which you live mark, can be a coaching table, can be how the TA supports in the classroom, can be a different level of depth to what other students in the class might be reaching, can be different resources or different exercises)

Specialist= interventions and higher-level support offered through the SEND team.

So, when you look at the Adaptive Teaching guide all the points remain valid as they focus on key strategies and teaching pedagogy you would deploy to ensure the engagement of the various students that make up your class.

To understand how to provide differentiation in your class for progress outliers which will require further thought and intervention, I have now created a separate guide which is Appendix 2.

Also connected to differentiation is the role of the TA in your classroom. If you have a TA supporting you with a class this provides a great opportunity for differentiation to be taken to a different level. To help with this, I have attached as Appendix 3 the Vision for the Effective Deployment of TA’s that you contributed to in the Spring term of 23. In this vision, within the teacher section it clearly outlines that the teacher should be actively working to support the lowest attainers in the classroom (differentiation), along with live marking to give dynamic feedback to these same students (differentiation). The TA is deployed to support and assist the learning, by checking on the progress of other students in the classroom and feeding back to the teacher where there might be gaps in understanding, thereby enabling the teacher to adapt the lesson (adaptation) to ensure the correct reteach of material that has not been properly understood in depth by the class.

Take your time to look at all the points on the vision document for TA deployment and try and assess how confident you are, that this vision is being put into action in your classroom, with the TA’s you work with. Likewise, TA’s, think about how confident you feel with the vision of your role and what areas you think you might need support with.

- Read More

March Blog 2024

Published 11/03/24, by James CollinsChallenging the More and Most able

In reading around the topic of More and Most Able (MMA) the theme of challenge recurs often.

“More able pupils in general welcome challenge and often like to take a lead in shaping their own learning”. (Cullen, Cullen, Dytham et al, 2018).

This document will look at how challenge can be provided for MMA students through different forms of scaffolding regarding key ideas on:

- Task design and differentiation

- Live Marking and Feedback

Task Design and Differentiation

One useful and popular form of scaffolding is a written resource: e.g. writing frames, sentence starters, single paragraph outline structures, checklists, vocabulary lists, and glossaries.

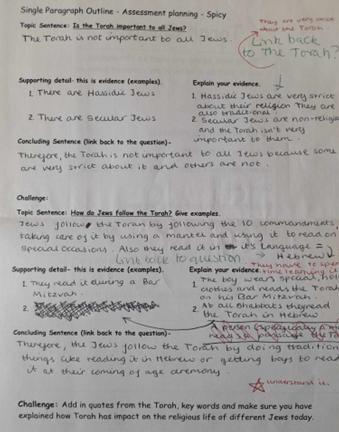

Single Paragraph Outline

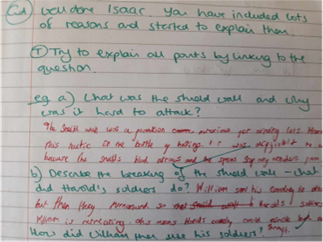

Here is an excellent example of how an SPO can be differentiated for more and most able students.

The questions and prompts are challenging and probing, asking the student to provide and explain their evidence, including using key vocabulary and quotes. The subject-specific vocabulary is used confidently and is extensive. The SPO then acts as a checklist for content.

The feedback also ensures the students include key points in their plan, which allows for a well written final answer.

Writing Frames

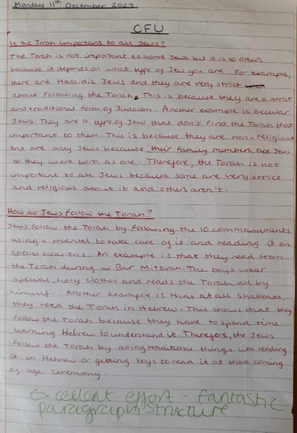

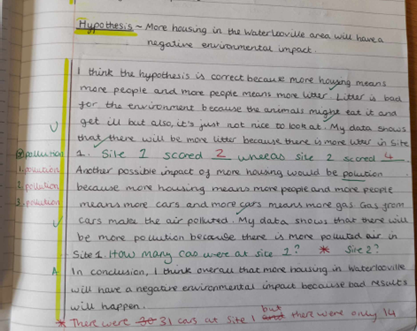

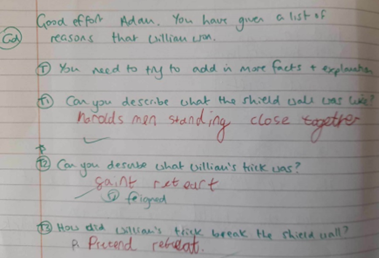

This next example from Geography shows how a task has been scaffolded with a writing frame to support an SEN student in assessing the hypothesis.

The open format of the MMA student’s work has challenged them to write the hypothesis review in full, together with using full sentences and subject specific vocabulary, thereby allowing them to consolidate these skills. The differentiation is clear.

Vocabulary

Vocabulary is key to comprehending and following a lesson. It should be introduced carefully to ensure understanding. It is also vital in expressing ideas and thoughts. Research has shown that explicitly teaching vocabulary increases the understanding and use of that vocabulary by students.

In addition to the Tier 2 vocabulary highlighted by Katy in her blog, it is important to teach subject-specific vocabulary. Explicit teaching may include the use of word lists and glossaries. It should also include students reading and analysing “The Big Question” and all keywords within it.

Students must understand the meaning of keywords, as well as examples of context. The MMA students should be given words that challenge them and allow them to express their knowledge in increasingly sophisticated ways.

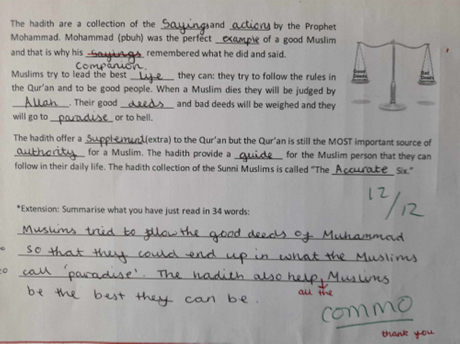

Summarising

This work is an example from an MMA student in a KS3 RS lesson. The student was given extension work; to summarise key information from a short piece of text.

Research has shown that summarising information is an effective and simple way to add challenge in the classroom, requiring a range of cognitive processes from selecting, organising, and integrating information.

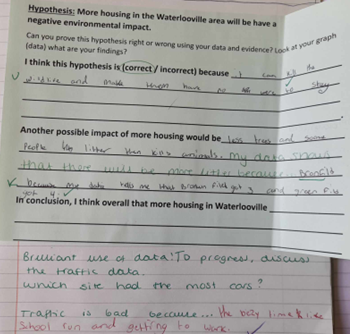

Live marking and Feedback

Live marking allows for immediate feedback and identification of misconceptions which can be addressed within the lesson. It allows us to identify students who require more support and also those who have understood the main content and require stretch and challenge.

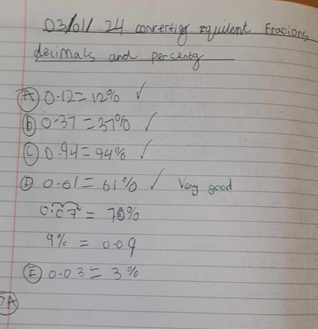

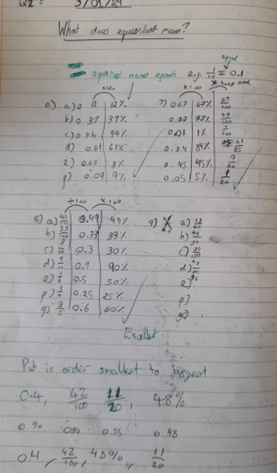

An excellent example from Maths shows how live feedback has been used to support a SEN student and challenge a MMA student.

Feedback is one of the most powerful techniques regarding students' outcomes and can be differentiated to support or challenge students. Below is an example of feedback from a piece of work in history given to a Year 7 SEN and MMA student where feedback questions have been carefully considered, allowing for greater depth and response for the MMA student.

An example from an English lesson shows how the question of ‘why’ can be used to stretch students. As well as the probing question why, which demands a considered response; the student must elaborate and therefore make connections with prior learning. This helps embed the knowledge and encourages critical thinking.

In this blog we have highlighted many different ways to construct and adapt planning or feedback to stretch the high attainers. We must get the level of challenge right for them, especially in our mixed-attaining classrooms.

- Read More

February Blog 2024

Published 29/01/24, by James CollinsHow to support students with revision

As part of our professional reading, James and I have recently revisited “The Revision Revolution” by Helen Howell and Ross Morrison McGill. The book discusses how students should be taught explicit study skills from Year 7, how to make revision enjoyable, and how to embed learning to help students grow into knowledgeable and informed young adults. This is precisely the aim of our developing blended learners programme (DBLP). The book provides a comprehensive guide on how to start and sustain a revision revolution in your school, building a culture of effective study that flows through all aspects of school life.

The key points of the revision revolution …

- It is to help students grow into knowledgeable and informed young adults, not just to help them pass exams.

- It is based on the idea that students need to be taught how to revise effectively, not just told to revise.

- It involves building a culture of effective study that flows through all aspects of school life.

- It involves using a range of study techniques, including active recall, spaced repetition, interleaving, and metacognition.

The study skills that we have taken from the book (and other sources such as teachertoolkit.co.uk) and built into the DBLP are:

- Active recall: This technique involves recalling information from memory without the aid of notes or textbooks. It helps students to identify gaps in their knowledge and improve their retention of information. This technique is based on the idea that the more you practice recalling information, the better you will be at remembering it.

- To use active recall, students can create flashcards with questions on one side and answers on the other. They can then test themselves by trying to recall the answer before flipping the card over.

- Another way to use active recall is to write out what you know about a topic from memory, and then compare it to your notes or textbook to see where you need to improve.

- By practicing recalling information, students are able to identify gaps in their knowledge and improve their retention of information.

- Mind mapping is a study technique that can help students to organise their thoughts and ideas in a visual way.

- Mind mapping involves creating a diagram that connects different ideas or concepts together using branches and sub-branches. Mind maps can be used to summarise information or plan essays.

- To create a mind map, start by writing the main idea or topic in the centre of the page and drawing a circle around it. Then, draw branches radiating out from the centre circle, each representing a sub-topic or idea related to the main topic. You can then add further sub-branches to each branch, creating a hierarchical structure that connects all the ideas. Mind maps can be created using pen and paper r using software such as Microsoft Word or online tools like Get Revising. Using different colours for each key concept can help organise your thinking and keep your ideas on track.

ACTION: As a tutor, encouraging students to do either of these techniques in their 10-minute chunks. Have some blank cue cards/mindmap templates ready for them to use. As a teacher, think about what homework could be based around this.

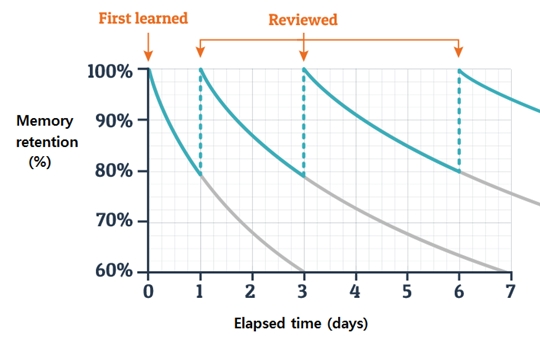

- Spaced repetition is a study technique that involves revisiting information at increasing intervals over time. It can be explained by the ‘forgetting curve’, which is an idea that has been around in psychology literature for over one hundred years.

- The forgetting curve was first introduced by Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885 and shows that the rate of forgetting is highest immediately after learning and then levels off over time.

- To use spaced repetition, teachers should plan to revisit key topics at certain points through activities such as ‘Blast from the past’ (Science) or retrieval quizzes.

- By revisiting information at increasing intervals over time, students can retain information in their long-term memory.

ACTION: When have you planned for this in your MTP’s and lessons? Have you considered what should be retrieved and when?

- Interleaving: This technique involves mixing up different topics or subjects during revision.

- To use interleaving, students can mix up different topics or subjects during revision. For example, instead of revising all the topics in a single subject at once, students can revise different topics from different subjects in a single revision session.

These techniques are particularly pertinent to year 11 as we move towards their final few months. I know a lot of you have planned a week-by-week schedule up to these mock exams and will be developing your final schedule based on the misconceptions shown through your marking. Please consider how the points above best suit your subjects.

- When is it best to make a mind map, and when should cue cards be used?

- How do I structure the week-by-week and class work to allow for spaced repetition?

- Read More

January Blog 2024

Published 09/01/24, by James CollinsHow to run a successful Parents evening appointment.

I have never done a blog on parents’ evening before, and with the next one rapidly approaching, I thought that this was a good time to share some useful advice for these evenings. When I was training to become a teacher (yes, that was a while ago now...) we were never trained for these evenings and it was literally a case of sink or swim. There is far more research out there now and I have investigated the National College for teaching to support this Blog. I hope it helps and if you have any questions, please feel free to come and speak to me or your HOS.

I have often thought that communication is what we do best and is probably a reason why we became teachers in the first place. We hopefully deliver clear explanations, impart knowledge, simplify complex concepts, give effective feedback and build positive relationships with those around us. We use our voice to manage behaviour and control situations, as well as to inspire and motivate.

However, for many of us, especially those new to the profession, the thought of holding conversations and giving feedback to parents/carers about their children and young people can feel particularly daunting, especially when we know that some of that feedback might be hard to hear. If this sounds familiar, this is the blog for you!

Firstly, you are not alone in feeling like this, as every teacher at one time in their career has had to face a parents’ evening for the first time, and most of us (if we’re honest) will remember feeling slightly intimidated by it. Secondly, feeling a bit anxious about a parents’ evening means that you care; you see its importance and you want to do a good job! The good news is there are lots of things you can do to ensure the experience is successful, purposeful and even enjoyable. It is an unpredictable night, but one we can plan for to support with the more challenging moments.

The benefits of a parents’ evening

A parents’ evening is a great opportunity to give positive feedback to parents/carers about their child and to give them an insight into their child’s life in school. Parents/carers ultimately want to know that their child is safe, happy and learning, and this is the opportunity to reassure them and to feedback what their child does well. There are always positives! This is your chance to show parents how much you value teaching their child. Watching parents light up with pride is such a rewarding part of our job.

We encourage students to accompany their parents/carers, so students get to hear the positive praise you are communicating. This can really boost students’ motivation and sense of pride which means they will continue to strive harder in class. Parents’ evening will also allow you to get to know your students even better, as you often find out things you might not have known.

Parents are often keen to tell you what their child is like at home or what their outside interests are, and this can really help you to build positive relationships with your students in class.

Obviously, one of the main purposes of parents’ evening is to feedback on students’ progress and what they are learning about. Make this conversation effective and purposeful by thinking about the key messages for each child. This is your opportunity to communicate what could be improved on.

Use this conversation to get parents onside and to get their support with their child’s learning or behaviour targets. You can even make suggestions about how they can support their child. Most parents/carers will receive constructive advice well if framed in a conversation which shows that, like them, you want the best for their child. (More about that later.)

How to prepare for parents’ evening

- Make sure the assessment record is up to date and be prepared to show the parents all the assessment and homework marks the student has received this year. Make sure the parent knows how to access this on ItsLearning and how to check what homework has been set.

- Know your students! I know this sounds silly, but go through your class list/s in advance of the day. Have ClassCharts up and what rewards and sanctions have been awarded in your subject area. Start with the positives or any improvements seen.

- Check the student books in advance, as you will want to share these with parents if possible. What can you show the parent on what the child is doing well, and where they can improve? Make sure the marking is up to date.

- Go armed with short notes about each student. Your conversations need to focus on student progress and targets, as well as their attitude to learning. Think carefully about how you will give difficult messages in a kind way.

- If you are a new teacher, practice and role play with your mentor some different scenarios. Practice how to conduct the appointment and iron out any issues.

Practical tips for the evening itself

- Look the part. You are the public face of the College on parents’ evening, so it’s a good idea to represent it as professionally as possible.

- Arrive ahead of time. Rushing into the hall to find a queue of parents does not give the best impression, so aim to dismiss students/students swiftly that day so you arrive before parents.

- Bring a drink and ensure you have eaten.

- Ensure you have a name sign on your desk, so you can be found. (This is usually organised by the support team.) You will need at least two chairs but be aware that some parents bring other family members and the student/s themselves. (Don’t be afraid to send the student away to sit in the waiting area if you wish to address the parents in private, though.)

- Have School Cloud open with the appointments but bring notes and data as well as paper and a pen to note down actions resulting from your conversations.

- Keep an eye on the time. If things look like it won’t be resolved, explain that you will call them the following week to speak about this further. Note this down on your pad!

Dos and Don'ts of an effective conversation

Dos:

- Do stand to greet the parents/carers. Shake hands, smile and thank them for coming, then invite them to sit down. They may be nervous too, so make small talk about things such as the weather or if they managed to find you okay. Help them relax. Make sure you have the right parents in front of you in case someone has not shown up. Most parents/carers offer the name of their child in the first instance.

- Do take a moment to read your notes and look at the student’s data before you start talking.

- Do start with a positive and a strength, even if the student is not making the progress they could: “His attendance is excellent, uniform impeccable and he is always on time.” “She wants to achieve and is keen to learn.” This part of the meeting is key, as it is here you show the parent that you care and want the best for their child. Parents will accept more constructive advice more readily if they know you are on their side.

- Do describe succinctly what the student has covered in terms of content but focus more on their progress. Use words like “steady progress”, “good progress”, “very good progress”, “excellent progress”. Give examples of what they have done well. Identify strengths where you can.

- Do describe what they need to do in terms of improvement, and that includes attitude to learning and things they need to work on more. Be specific! For example: “If he is going to achieve a grade 7, he needs to use a range of different tenses in his written and spoken work. He needs to do some independent learning on verb formation in French so that it sticks.” “She always starts off the lesson being really interested, but she has difficulty maintaining focus. We have started using a sand timer and a checklist to help her concentrate. It would be good if she used these at home too, when doing homework.”

- Do take time to listen to parents/carers and their concerns. This is a two-way conversation. Make notes of actions to take forward. This will mean they see you are taking their comments on board.

- Do be truthful. Do be kind.

Don’ts

- Don’t be overly negative or use negative language, e.g. “lazy”, “apathetic”, “rude” or “weak”.

- Don’t be excessively positive unless it’s true.

- Don’t comment on things that can’t be changed, such as a child’s personality. What is the point of telling a parent that their child is “quiet” or “talkative”? Being quiet doesn’t mean you aren’t learning and being talkative doesn’t either.

- Don’t be vague. Avoid, for example: “They need to work harder.”, “They need to add more detail.”, “They need to keep going.” Rather, be specific about actions which can help the student/student progress: “They need to be spending and hour each night using the revision techniques we have been using in class.”

- Don’t be afraid to get support if you need it. You can refer parents/carers to other colleagues if you need their expertise. SB and I are in the foyer in the Performing Arts if needed, and please direct any parents who are not happy to us.

Dealing with negative feedback or bigger issues

It’s worth remembering that the majority of parents/carers are enormously grateful to teachers and often admire us for the job we are doing. Parents/carers will often feed this back and thank us for our support, which makes parents’ evening a really enjoyable and affirming experience.

On occasion, parents may use parents’ evening as a forum to voice their concerns. This is fine, but if a situation or concern is serious or complicated and can’t be resolved during this 5-minute meeting, don’t be frightened to communicate this.

- Firstly, listen carefully to the parents’ or carers’ concerns. Give eye contact and nod. Make notes so the parent/carer knows you’re taking their concerns on board.

- Express your concern: “I am sorry to hear that.”

- Ask what the parent would like to happen to resolve the situation (whilst not promising that you will follow their suggestions). If you can deal with their concerns in this meeting by suggesting some actions you could take, then do so. For example: “Okay, let’s try moving her to a different seat, so they are sitting apart. That just might resolve the problem.” However, if the issue is greater than that, explain that tonight’s meeting is only a five-minute slot for feedback on their child’s progress, so an additional meeting will need to be booked which might involve other colleagues, such as the Head of House.

- Try to get the meeting back on track by updating them about their child’s progress and wellbeing in College.

Don’t hesitate to seek help from colleagues if parents become hostile or personal. This is very rare. If you expect this may happen in advance of the parents’ evening, ask that another colleague is present with you when the meeting takes place such as your HOS or SLT.

Difficult questions

You may come up against some tricky questions. However, if you plan and prepare well, you can anticipate them and be ready with an answer. Remember, being tactful and diplomatic is key, whilst remaining honest and truthful.

Top tips for dealing with difficult questions

- Anticipate the difficult questions that could come up and plan your responses to them.

- Seek advice from experienced staff about experiences they’ve had, and how they would answer tricky questions.

- Don’t be afraid to say you don’t know the answer to a question. Simply make a note of it and promise to get back to them with an answer.

- If a parent/carer asks directly about how their child or young person is performing in relation to the rest of the class or year group, you need to be truthful but tactful. You could refer to age-related expectations too. If a child is below expectations, you can still communicate this in a positive way. For example: “They are not quite where they need to be, but I am confident with the support we have in place, they will continue to make progress.”

After parents’ evening

Reflect on the evening and dwell on the highlights first. There will definitely be some. Think about what you handled well and embrace the areas you are going to work on further. Seek advice from others and share your experiences with your colleagues on what went well, what was tough and what you learnt.

Remember to follow up on those actions you promised you’d do, so parents know you are true to your word.

- Read More

December Blog 2023

Published 11/12/23, by James CollinsAs we approach the end of another long winter term, it is a good time to reflect on the successes within our classrooms during 2023 and consider what we need to do as a staff to improve as we dive into 2024. We all know this will be an inspection year, but that is something teachers do not need to worry about, as we know our high standards will shine through for any team that visits us. A couple of Heads of Subject have asked me to write down some key things we would expect to see in every lesson, and what the expectations are of our teachers, so everyone is on the same page. Below is a summary of all our policies in a handy guide.

- Feedback and marking

HOS would expect to see the students given feedback every two weeks in core lessons, and 3 weeks in foundation lessons. This would be at least one piece of student work marked, with formative feedback to help the student improve that piece of work. This could be done either on itslearning or in books. We would then expect the student to respond and the teacher to check this. No need to mark that response, just acknowledge with tick or como’s. In the books, the teacher marks in green and students respond in red. There is a need to mark for literacy when you do this, so please refer to Katy King’s emails on this- I got my TA to help me with this, which works well.

We are pushing the idea of ‘live marking’, where you will give students instant feedback in class, and they do their response at that time. Plan approximately 15 minutes of independent time where students can work without you, and you go around and mark some books and get them to respond straight away. This means that you don’t have to take any books home with you! The books or itslearning plans should have a clear footprint in of teacher feedback and how this has led to progress. No need to stamp ‘verbal feedback’ in books, we know you do that all the time!!

- Planning

We expect all planning to be done on itslearning and plans to be made live for the students to access. We would expect teachers to show the plans to the students during the lesson and teach from itslearning, bringing up any documents needed. This will build up good habits for teachers and students in the consolidation of Blended learning. All departments have their plans now on itslearning, which are sequenced and built around MTP’s and then components of learning. All components should be based around a ‘Big Question’, which students should be checked on at the end. Teachers should have considered the key knowledge and skills needed and what vocab is vital to teach to the students to help with their understanding. Activities should be planned out to support all learners, with consideration on how to extend and support where needed. Homework should be planned in at regular intervals and checked/rewarded and teachers should reflect on their learning at regular intervals (Progress partner meetings as a minimum). We should plan regular assessments to check on learning, and then consider how our plans should reflect this in future. We would expect at least one homework and one assessment in each half-term to be reflected in the assessment record on itslearning. I know many of you do far more as this really helps build up a picture of how that student is making progress.

- Teaching

We have the ‘Excellence as standard in the Crookhorn classroom’ guide, which is our absolute bible when it comes to what pedagogy is expected in the classroom. Here are the biggest vitals as a quick reminder;

- Welcome at door-check uniform and make sure the start of lesson is ordered. Have the ‘Do Now’ task ready for them, whilst you take the register. This could be a quick retrieval activity from previous learning. It should be an independent task to keep them quiet. Great to do on Mini whiteboards (MWB) so you can see what they are doing.

- Go through Big Question for this component of learning- and how they will develop their knowledge to answer this over a learning period. Explain how their learning will be checked at end of lesson. Consider things such as exit tickets or a task to show they have worked towards this outcome.

- Get as much data as possible from students when it comes to checking what they have learnt. If they are asking questions, or checking they have understood something, there is no point going to hands up and then checking one person’s understanding. Again, things like MWB will give you the whole classes understanding quickly, or live marking will give you a greater understanding whilst they are working on a small task. There is no need for students to be shouting out at you so make sure this is not tolerated.

- Consider using ‘Think, Pair, Share’ when it comes to checking understanding. Get students to write one or two bullet points on MWB, then share with their partner and discuss who has a stronger answer, then get them to hold up boards, so you can see which partners have answers you want the whole class to hear and discuss.

- Use of the visualiser is really powerful, and a great way for you to model. Also, a great way to share students work, and get them to consider ways to improve etc. The ‘I do, we do, you do’ model should be standard practice.

- Encourage discussion where possible, following the Crookhorn rules for discussion.

- Move around the room as much as possible, place yourself where needed and be full of positive praise for students when you can be.

- Have your green pen in your hand when moving, get into the habit of giving live feedback with students in the moment.

- Consider live differentiation in every lesson- and how this can be done. Start with CFU, and plan how to differentiate from there. If certain students don’t get a task, consider moving them onto a table and then working with them whilst others are working on a greater depth task. If this is not possible to move students, then choose these students for live marking immediately, and give them extra pointers to help them. Extra support such as them using BYOT to check their itslearning plans, use of exercise books and resources on itslearning or access textbooks/help sheets that you have pre-planned will help.

I hope this ‘quick guide’ helps remind you of the key expectations of what high quality teaching looks like at Crookhorn, but if you have any questions please do ask your HOS, coach or myself.

- Read More

November Blog 2023

Published 28/11/23, by James CollinsI know many of you have been eagerly anticipating the next T+L blog, and here it is! Over the last couple of months I thought I would let the excitement grow, ready for this edition beautifully written by Katy King and Libby Osbourne. These two ladie - Read More

May Blog 2023

Published 09/05/23, by James CollinsThe importance of literacy in maths

“Strong literacy skills give students a greater opportunity to improve their fluency of content. This then enables students to build their knowledge and understanding within the content and problem solve to a much deeper and greater level both in your subject and make cross curriculum connections.” Mark Kyrillou (2023) (James always like research in these blogs!)

In Maths, you would think Literacy has a minor part to play and the only letters we use are “x’s” and “y’s” in algebra. People don’t realise, but Literacy in Maths is equally as important as getting the sum correct because without knowing what they are answering or why they are answering a question, we can’t expect them to be able to get the answer correct.

“Without the input of deep, contextual learning at the beginning of every learning episode, students only learn the content on a low superficial level. Without Literacy being taught well, the content has no meaning and students do not understand or appreciate why this learning episode has its place. The understanding of keywords and context of the literacy give the foundations and building blocks for students to understand the content.” Failed footballer and male model Mark Kyrillou (2023).

So what do we do in the classrooms to promote literacy, and what can every teacher consider?

Teacher prompts

- We are considering how to get students to meet the complex demands of unpacking worded problems in Mathematics through discussion.

- We have really considered the use of the ‘group discussion rules’ introduced to the College. Since we moved to tables it has helped us get the students to talk about their mathematical thinking and literacy demands of the subject. This needs to be planned, and we have found it so important to give them time to do this. Our next step is to consider how we structure these discussions, and we are looking into talking frames in the future.

- We encourage students to debate possible solutions to problems in Mathematics and ask them to work together in groups to come up with different answers.

Strategies used

Without meaning to patronise anyone here, I know many of you use these strategies, but I thought I would share some of the strategies you can use:

Word searches – all the keywords they could use with this component of learning can be put in a word search. This helps with spelling. We then have a class conversation with students finding out the definitions of the keywords.

Scrabble block – you get students to give you 10 letters at random, and you write them on the board. They then have to come up with as many words as possible linked to your topic and explain how that word is linked to the topic.

Recap (Starter) questions – include definitions or contextual question at the beginning of your lesson which gives students the opportunity to either recap or explore information.

Examples I use in my learning episodes:

- Where are decimals used in real life? Where have they used decimals or percentages in real life?

- Give 2 definitions of the word “mean”? (Mean is the average in Maths but also used as a description of me!)

- Give an example of how a Scattergraph is used in Geography. (I would have already taught them that Scattergraphs shows the relationship between two variables)

- Define the word ‘multiple’ or give an example?

- What measurements and units are used in Catering? Or can you put these measurements used in Catering in order from biggest to smallest?

- Where are percentages (or figures/graphs/tables whatever I am teaching) used in Sports data?

Diagrams with no questions - I’ll put a diagram of a triangle or graph on the board and students have to come up with 5 questions they could ask about that particular diagram – they are then having to think of the keywords themselves.

Match up the keywords with the definitions - Literacy is treated with as equal importance as any question they are answering from the task given. At the start of the lesson and before I explain how to solve any question, a few minutes are spent defining the keywords – students write these with me with the same expectation of learning as the Maths content. Planning this into our retrieval thinking means we know this will be recapped on in future learning.

I am really keen to develop cross curricular links between subjects and if anyone has any suggestions or strategies they use, I am always looking to develop my teaching and work with the T+L team here to support colleagues. Please feel free to share your ideas with me no matter how unnecessary or basic you think your idea is.

Mark Kyrillou

Failed footballer/model/genius but happy teaching Maths!

- Read More

April Blog 2023

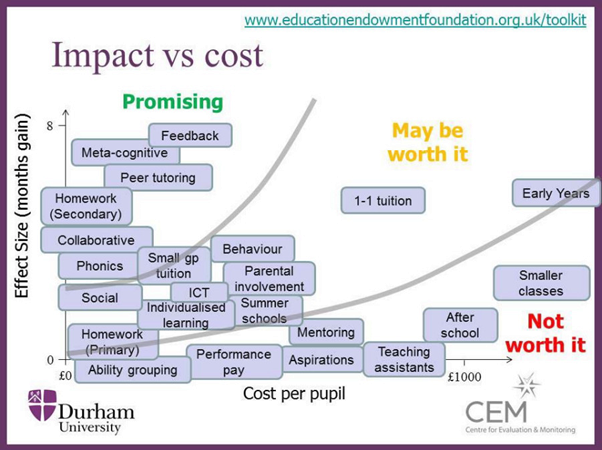

Published 20/04/23, by James CollinsDuring this holiday, the Senior Leadership Team are reading a book called ‘Reaching the unseen children’ by Jean Gross. It looks at practical strategies for closing the stubborn disadvantaged attainment gap, with particular focus on underachieving boys (and we can all think of students like this in our classroom!). Gross references research heavily, and in particular, the EEF teaching and learning toolkit. I want to draw your attention to some of the strategies that are highlighted and what we should be doing in our classroom to implement these effectively.

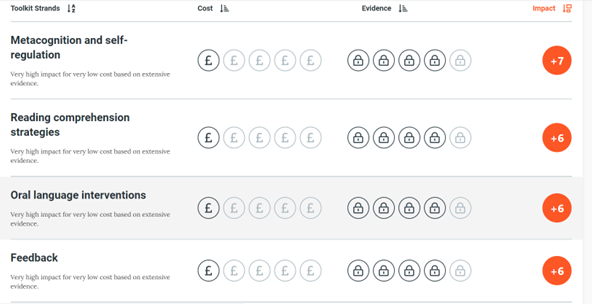

The following screenshots of this research, which I am sure many of you have seen before, highlight the importance of intervention. The Toolkit looks at each of the key interventions that schools use, how much they would generally cost (£) and then the strength of the research behind this (Padlock). The number in the circle at the end is the months of progress an average child will make compared to a child who does not receive that intervention. The link below will allow you to go onto the website and have a more detailed look if you would like.

https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/teaching-learning-toolkitLet’s take a look at some of the strategies mentioned at the top of the league for promoting progress and what we should be doing in the Crookhorn classrooms.

Feedback: "Feedback is information given about the learner’s performance relative to learning goals. It should aim towards (and be capable of producing) improvement in students’ learning. Feedback redirects or refocuses the learner’s actions to achieve a goal, by aligning effort and activity with an outcome. It can be about the learning activity itself, about the process of activity, about the student’s management of their learning or self-regulation or (the least effective) about them as individuals. This feedback can be verbal, written, or can be given through tests or via digital technology. It can come from a teacher or someone taking a teaching role, or from peers."

Crookhorn: We promote many different ways of providing feedback, including through exercise books and ItsLearning. I believe that live feedback is best; the student is in the process of learning and any corrections or adjustments to their learning at that point should have most effect. We also have done some training with our TAs, and if you are working with a TA and have given them support with this, they could also help with live marking. Many teachers are now using ItsLearning to provide feedback, with audio and video feedback being used to help with teacher workload. If you need any support with this, please see your coach.

Homework: "Homework refers to tasks given to pupils by their teachers to be completed outside of usual lessons. Common homework activities may be reading or preparing for work to be done in class, or practising and completing tasks or activities already taught or started in lessons, but it may include more extended activities to develop inquiry skills or more directed and focused work such as revision for exams."

Crookhorn: We believe that homework should be set consistently across the 5-year groups. If students are not consistently set homework for your classes in KS3, they will not be in good habits as they move into KS4. Homework should be planned into your components of learning and should be set through ItsLearning. The use of SENECA or ItsLearning self-marking tests should be used, to make sure teacher workload is not increased. Prepare students for upcoming assessments in KS3 by getting them to study for this using the revision techniques we promote, as again, this will promote good habits for them when it comes to GCSEs.

Reading: "Reading comprehension approaches to improving reading focus on learners’ understanding of the text. They teach a range of techniques that enable pupils to comprehend the meaning of what is written, such as inferring the meaning from context, summarising or identifying key points, using graphic or semantic organisers, developing questioning strategies, and monitoring their own comprehension and identifying difficulties themselves (see also Meta-cognition and self-regulation)."

Crookhorn: We all have a responsibility to improve the reading comprehension of the students in our class. It can’t be seen solely as the task of an English teacher, or Cheryl, Sarah Woods or Ellie McBride with their specific interventions and mentoring. We are moving DEAR time from after Roll Call over to the morning which will be linked in with tutor time to increase the profile of reading and its importance with students and staff. Teachers should think about their planning and consider where there are opportunities to enable students to read, the potential barriers they may face and then develop student understanding of what has been written. We have asked HOS to choose words from out Tier 2 vocabulary lists that teachers will be promoting, to develop further students’ understanding of key words, to support them with their reading.

Collaborative learning and oracy: "Collaborative or cooperative learning can be defined as learning tasks or activities where students work together in a group small enough for everyone to participate on a collective task that has been clearly assigned. This can be either a joint task where group members do different aspects of the task but contribute to a common overall outcome, or a shared task where group members work together throughout the activity. Some collaborative learning approaches also get mixed ability teams or groups to work in competition with each other, in order to drive more effective collaboration.”

Crookhorn: By getting students to work together, and talk to each other about their learning, we will see progress made. As a College, we have followed the research and introduced mixed attaining teaching in many of our classrooms (see below), and the classroom layout you have in your classrooms should facilitate students to be able to easily discuss learning. Plan for this, and don’t forget the ground rules we have in place to make sure that the students discuss learning in the right way. We want to develop skills that students will need for the rest of their lives, not just to pass their GCSEs! Working together in a team, presenting ideas, looking at two or more points of view and realising that others have a different take to you are all strategies we want our children to have.

We have an amazing group of teachers at Crookhorn, and our students are very lucky to have such a hard-working, determined, and self-reflective collective of staff to support them. When you have your next coaching session, please use this blog to reflect on where you stand with each of the strands I have highlighted, and what you could do to improve your practice in the coming months. Have a great summer term, and if you have any questions or reflections on this blog, please do not hesitate to ask.